|

San Ignacio MiniThe Jesuit social experiment“…the story of the labours and achievements of the disciples of Loyola in these innermost recesses of the continent is to me a singularly picturesque and fascinating one. The saddening reflection of how utterly the tide of intelligence and practical civilisation brought in by them has receded from these regions, to be replaced by a barbarism trans- parently veiled under the least attractive forms of modern democratic teaching and so-called progress. The golden age of the … Guarani was unquestionably under Jesuit rule, and it may be doubted whether the proud privileges of Argentine citizenship now enjoyed by the remnant of the race have brought to it advantages to be compared with the benefits of the firm and peaceful sway under which its forefathers throve and multiplied.” Sir Horace Rumbold, The Great Silver River: Notes of a Residence in Buenos Ayres in 1880 and 1881

A mere 75 years after the founding of the Society of Jesus - the Jesuits - the order embarked on a bold social experiment in benevolent theocracy not equaled in history before or since. Horrified by the wholesale destruction and enslavement of the indigenous peoples by Portuguese and Spanish colonist in the New World empires, the Jesuits persuaded the King of Spain in 1609 to grant the Society a vast region which today comprises southern Brazil, Paraguay, Uruguay and northeast Argentina. This was the homeland of the Guarani, an ancient culture of hunter-gathers. (Lands in the northwest of Argentina were granted as well leading to the establishment of the great University of Cordoba.) Over the next 150 years, the Jesuits established a series of missions - actual fully functioning cities - encompassing a large church, hospital, school, craft workshops, housing for all and irrigated agricultural and pasture lands. The Guarani were not forced to move into the missions, but thousands did.

The missions were a socialist theocratic state yet, although the Jesuits baptized all those who lived in the mission, they did not suppress or punish native spiritual beliefs. Since the Jesuits were in the forefront of advanced humanistic education, they realized a commonality among religious traditions and blended indigenous beliefs with their Christian counterparts. This is especially true in the extensive carvings and decorative motifs on the red sandstone buildings all constructed by Jesuit trained Guarani craftsmen. All residents of the mission worked in the tupambae lands, property of the community, 6-hours a day (the average European was working 12-14 hours) and all the products which they produced were fairly divided among them. The Guaraní became highly skilled in handicrafts, sculpture, woodcarving, metal work, jewelry, and produced such advanced products as watches and musical instruments. The Jesuits even used their natural singing and musical talents to create new liturgical compositions sung and played by all-Guarani choirs.

One of the most remarkable achievements was the creation of a Guarani dictionary to teach a written form of the language in the mission schools. The Guaraní mission society was the first in South America to be entirely literate in their native language. At their height in the 18th century about 30 missions had a population up to 20,000 residents each. (San Ignacio Mini had a population of over 4,000). Unfortunately, Jesuit success and prosperity drew the ire of ambitious colonizers who persuaded the King to strip the Jesuits of all their property and expel the order from all New World lands in 1767. The wealth of the missions was disbursed/stolen, the many structures dismantled for their building stone, the remainder swallowed by the jungle. The Guarani returned to the forest and to a life of abject poverty and exploitation on the plantations and in the mines.

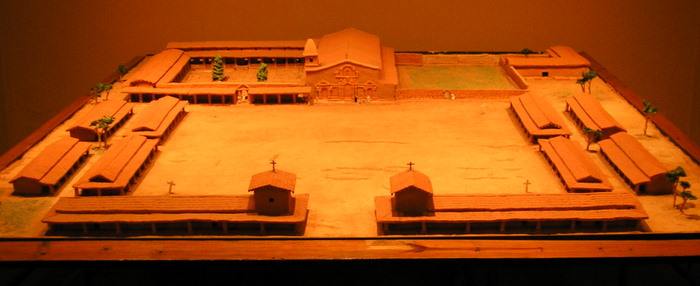

(Museo Jesuítico de San Ignacio Miní)

The history of this tragedy is accurately told in Roland Joffé’s 1986 film The Mission - one of most beloved films in Argentina. The ruin of San Ignacio Mini is considered the best preserved of the missions and its rescue started in the 1940’s. In 1984 the ruins were declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. The mission is open every day from 9:00 am to 7:00 pm, admission is AR$10 (US$2.65). If you wish to enjoy the mission in solitude, it is best to arrive early since by 11:00 AM hordes of tour busses arrive. Or go after 4:00 PM when the busses leave. After paying admission, you enter the Museo Jesuítico de San Ignacio Miní. The museum is well laid out and fully explains the workings of the mission as well as containing remarkable art works produced by the Guarani. Guided tours are available, but it is easy to wander the mission grounds and buildings with multi-lingual signs providing information. You will see ongoing restoration projects to support the fragile sandstone walls and preserve the carvings. But most of all you will marvel that such a remarkable social experiment could succeed for so long in the middle of the jungle.

(San Ignacio Mini at its height ca. 1750)

|